Most learning and development teams approach manager development the same way: build an academy, design some workshops, maybe add a leadership program. But what if the entire premise is wrong?

That's the argument Drew Fifield has been making throughout his career at companies like Meta, Nike (Converse), and, most recently, Axonius. His approach challenges the traditional L&D playbook by treating manager development not as a training problem, but as a systems problem.

We sat down with Drew to understand how he thinks about manager enablement, what makes it different from traditional development approaches, and how to actually build systems that help managers get better at their jobs.

From development to enablement: a fundamental shift

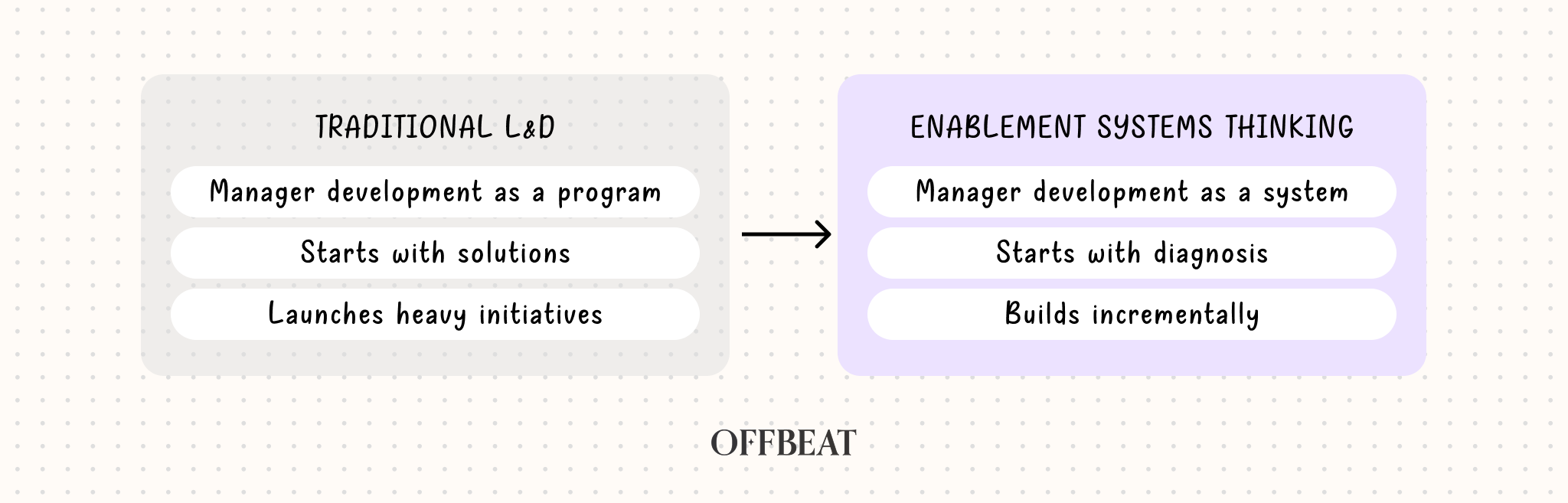

The distinction between development and enablement might seem semantic, but for Drew, it represents a complete reimagining of how L&D teams should operate.

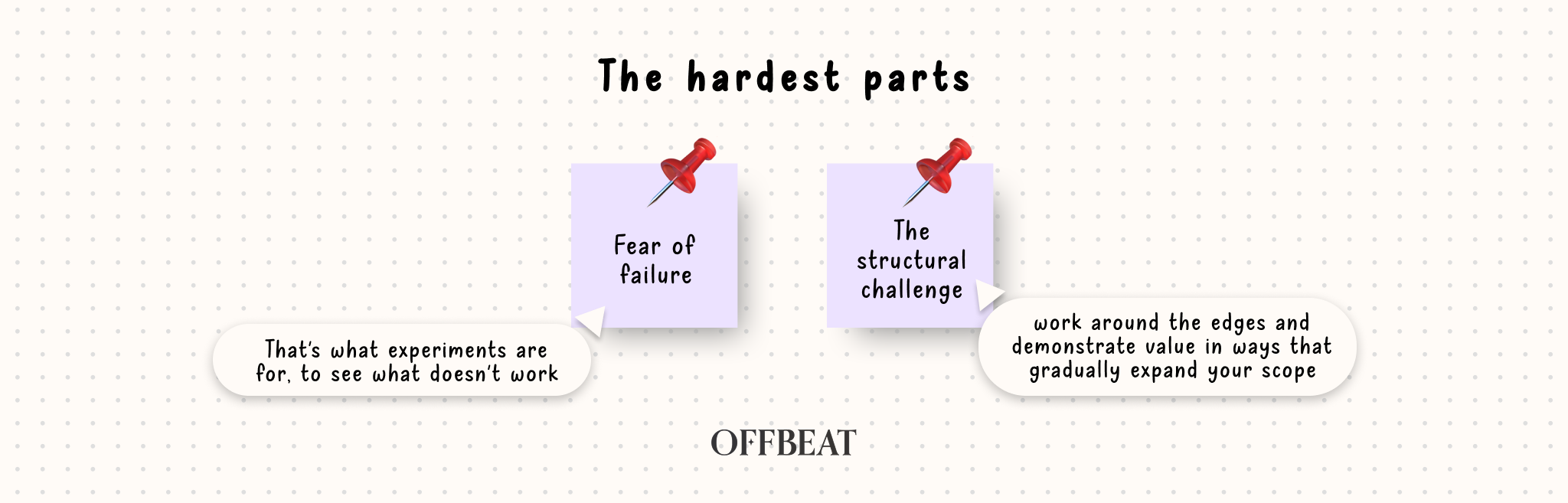

"I'm not an anti-development or learning person, but I am an anti-academy person," he explained. The problem isn't learning itself, but the assumption that learning programs, delivered in isolation, can solve manager performance challenges.

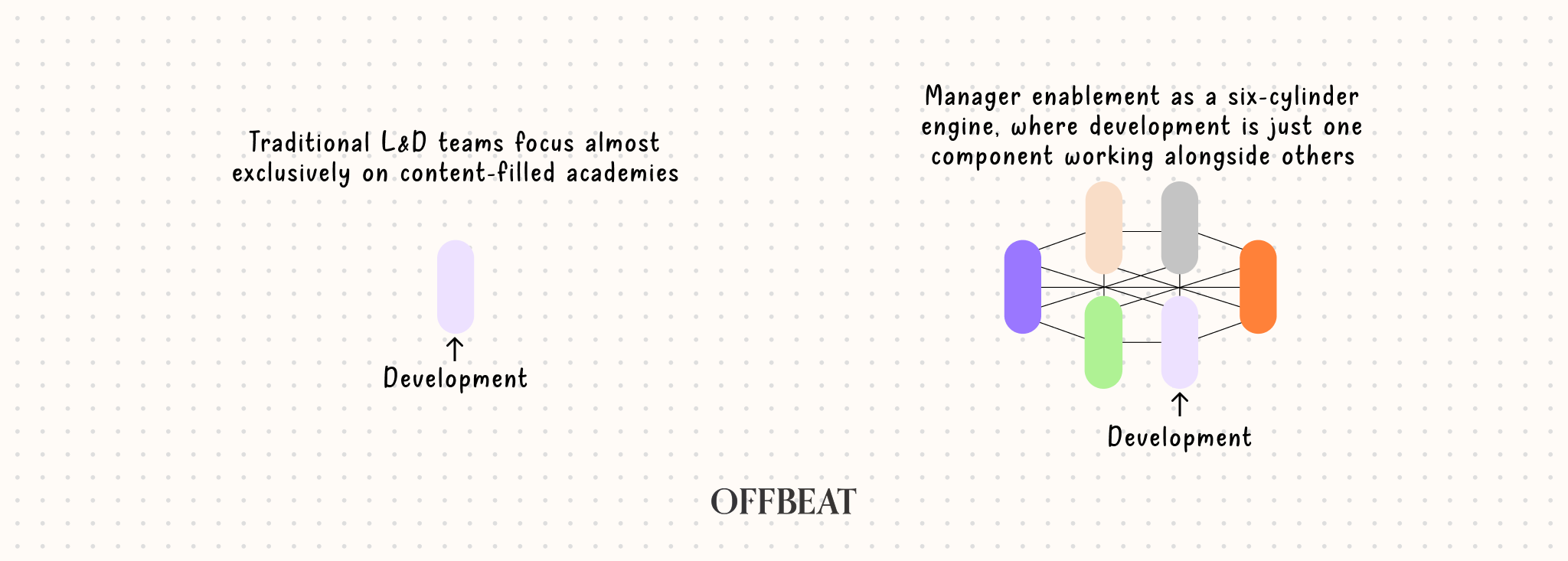

Traditional L&D teams focus almost exclusively on content-filled academies: workshops, courses, leadership programs. But good content is just one cylinder in a much larger engine. And when you only focus on that single cylinder, the engine doesn't run well, no matter how perfectly tuned that one piece might be.

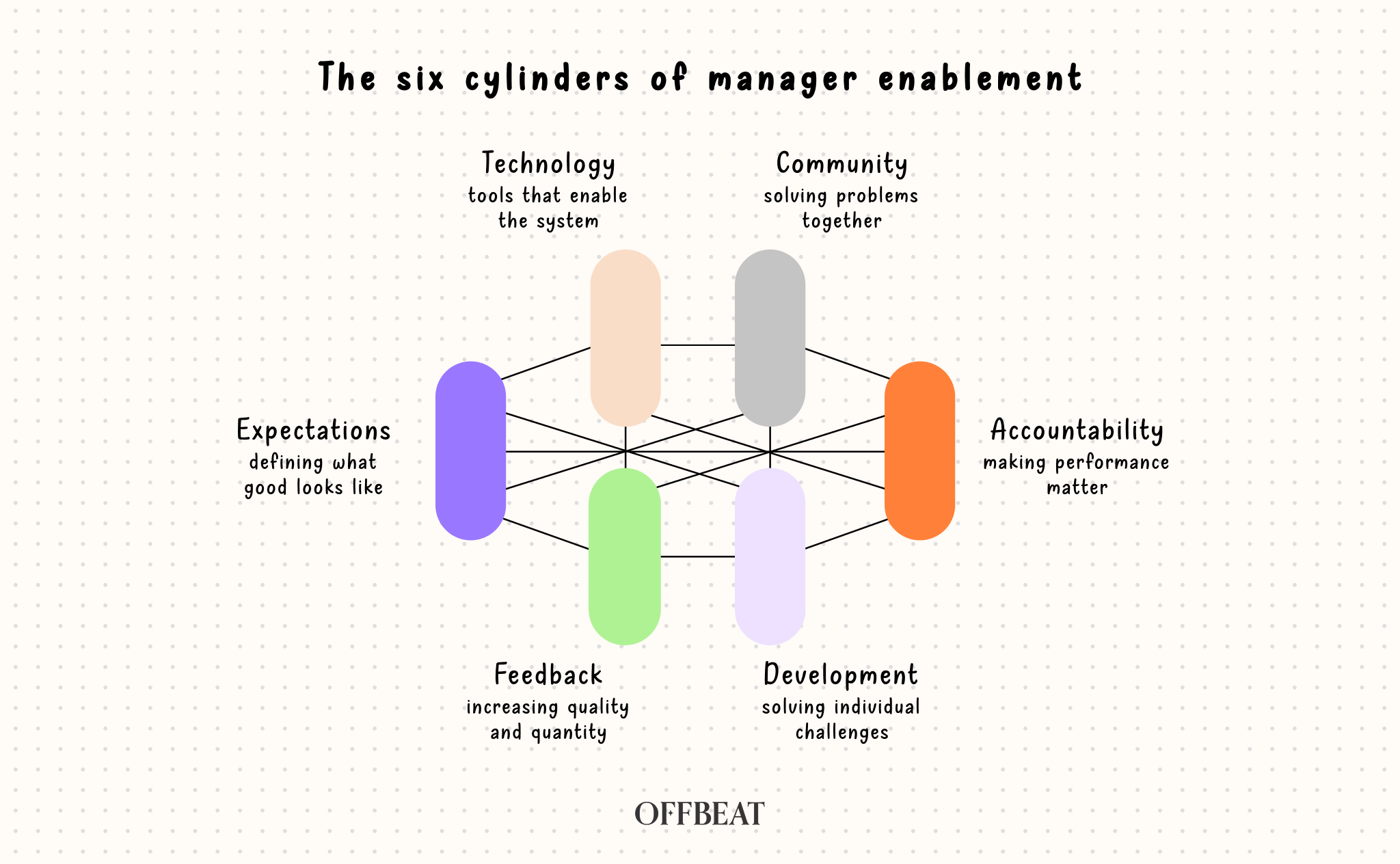

Drew thinks of manager enablement as a six-cylinder engine, where development is just one component working alongside expectations, feedback, accountability, community, and technology. "You can get moving if you've got three of these working," he said. "But thinking of them one at a time, thinking just about the content won't solve the manager problems that I know companies are trying to solve."

This systems thinking approach, borrowed from sales enablement and go-to-market teams, and grounded in social cognitive theory, addresses the reality that manager performance isn't just about what managers know. It's about what they're expected to do, what feedback they receive, how they're held accountable, who they can learn from, and what tools support their work.

The six cylinders of manager enablement

Drew’s framework breaks manager enablement into six interconnected components. Not all need to run at perfect efficiency simultaneously, but you need at least a few working together to create momentum.

Expectations: defining what good looks like

The foundation starts with clarity.

For managers, this means explicitly defining what good management looks like at your company. Not generic leadership competencies, but specific expectations tied to your organization's context and values. “It's important to take a data-backed approach, by which I mean rooting expectations in the day-to-day realities of managers. That means looking at engagement, performance, and effectiveness data to understand the challenges managers actually face and how they overcome them.”

At Nike, Drew spoke to managers with good business results and good people results about their managerial highs and lows at the company. “We used that data to define the habits of high-performing managers, a shared language of their expectations.”

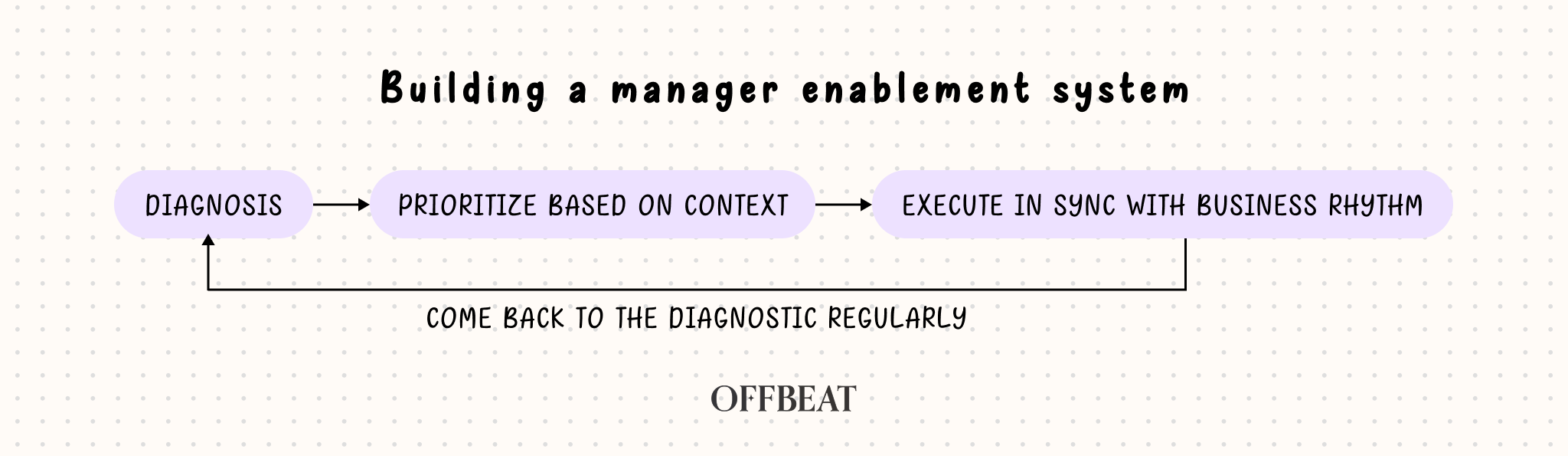

At Axonius, Drew found that manager expectations were already in place and clear enough to build on. The effort required to change them would have been greater than the impact, so he kept the existing framework. This kind of pragmatic assessment, understanding what's working well enough versus what needs urgent attention, is central to his approach.

Feedback: increasing quality and quantity

Once expectations are clear, managers need to know how they're performing against them. This is where most companies fall short.

When Drew joined Axonius, there was no manager feedback system at all. “When I joined, I asked what I often ask: ‘Do managers get direct feedback from their teams?’ and I heard what I often hear: ‘no, because most managers aren't ready to take action on that feedback.’

The logic, when applied to any other function, wouldn't hold up. “You would never hire a finance director who wasn't able to take action on feedback about the quality of their analyses. And you would never hold back, pointing out the errors and how to correct them.” Yet it's exactly how many companies approach manager feedback. They worry managers aren't ready to receive it, so they avoid giving it entirely.

Drew’s goal isn't perfection but progress: "How do we increase the quality and quantity of feedback that managers receive about their performance against those expectations?" Sales enablement teams understand this instinctively. L&D teams need to adopt the same mindset.

"It's just like training an AI model. As the more data managers have, the more they can improve their outcomes."

Development: solving individual challenges

Development is critical, but it has to work differently than most L&D teams approach it.

"What development has to be is specific to the challenge that that individual is facing, and that’s different from the challenge that the company's facing, or that the team is facing," Drew explained.

This means moving away from static workshops and templatized content designed for entire manager populations toward more targeted, personalized interventions.

At Converse, this looked like group coaching labs that were "part learning, part diagnosis" where managers worked through feedback they received from their team. "We weren’t just talking theoretically about feedback, we were reflecting on and analyzing feedback in their hands, right in front of them."

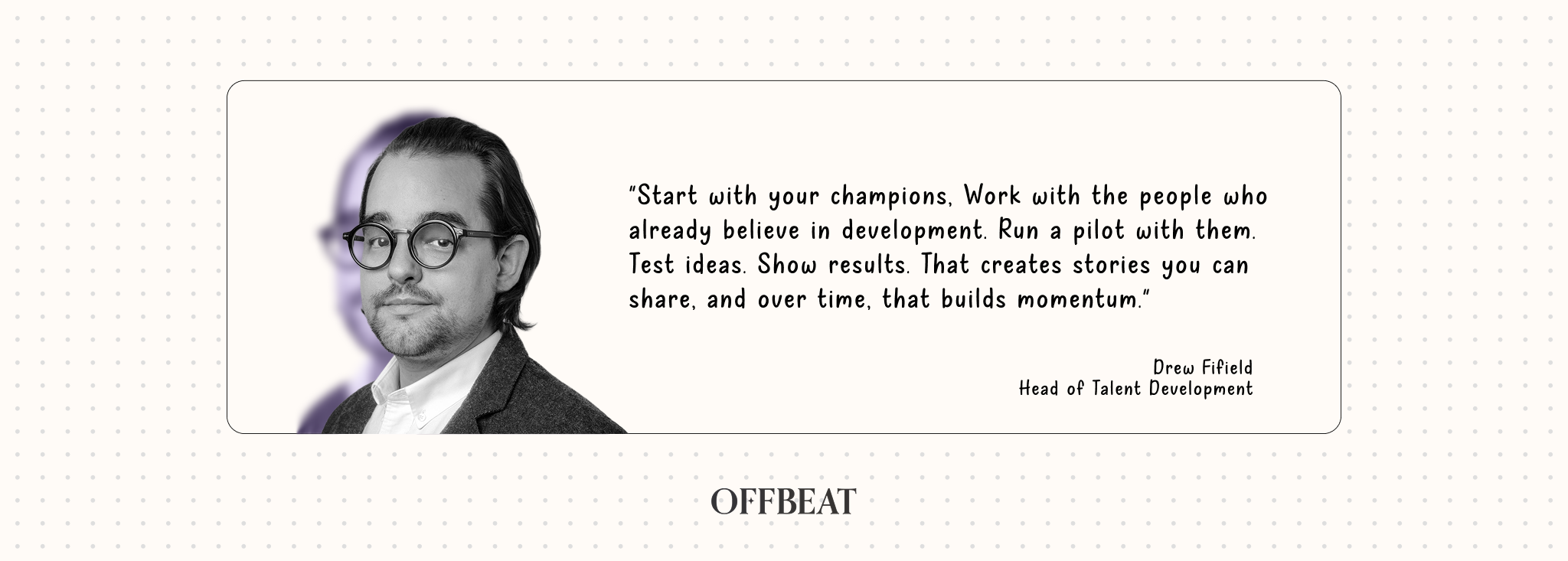

At Axonius, Drew created a Gemini-powered reflection tool paired with one-on-one manager coaching. "Those dollars were easy to find because I'm not paying for an LMS and I'm not running workshops," he said. "So those dollars are there in the company. I think we're just spending them in the wrong places."

The investment thesis was straightforward: "Every dollar spent here in a one-on-one, tailored conversation with an expert that knows our company and what my challenge is, will be of higher value than any workshop that we can deliver. Even if it feels like that's more scalable, the output is that individuals will perform better every time if we approach their individual challenges in a 1:1 setup."

Does this mean workshops have no place? Not at all. But they need to be targeted to specific cohorts facing specific challenges.

At Axonius, Drew ran a workshop specifically for new managers who hadn't been part of the feedback system yet. "I knew exactly what their challenge was." The workshop got them familiar with expectations, included AI-powered role plays for practice, and connected them with coaches for targeted support. “That’s what the workshop looked like. It was still worthwhile; the investment made sense because it was tailored to a smaller group of managers who all shared the same challenge.”

.svg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)